The government’s draft plan to fund future NBN wireless and satellite costs via a new ‘broadband tax’ has one problem: it aims to replace an existing scheme that hasn’t been given a chance to succeed or fail.

Under the original NBN business model, the network builder set a uniform wholesale price that contained an embedded cross-subsidy.

Put simply, fixed-line users in high-value (mostly metropolitan) areas would pay more than it cost to service them, and that in turn would fund the build and maintenance of the NBN in “non commercial” regional and rural areas.

The government now says that arrangement isn’t feasible; that competition for customers in high-value areas means NBN Co must drop its wholesale price there to compete with private operators like TPG.

No uniform wholesale price, no embedded cross-subsidy.

But a reconstruction of NBN Co’s three-year construction plan by iTnews raises significant questions about whether the existing cross-subsidy arrangement has been afforded a chance to succeed.

Further, justifications for the introduction of a broadband tax to replace the cross-subsidy raise questions about just how much competitive duress NBN Co is really under.

The net benefit of the tax over the existing cross-subsidy could be marginal, and the government admits it may not stop any future calls on the budget to fund fixed wireless or satellite upgrades. In which case, is a change really even necessary?

Let’s deal with the issue of whether the cross-subsidy has been given a chance first.

To do that, it’s useful to understand how the cross-subsidy actually works.

While ostensibly a way for metro NBN users to pay for the regional and rural rollout, it does not operate like this in practice.

NBN Co doesn't classify areas of the rollout nor individual premises that will pay the cross-subsidy.

It's just assumed the areas that do will be cities where connections would be most profitable; however it is possible that regional FTTP users, for example, already contribute to the cross-subsidisation of less economically viable connections.

iTnews understands the cross-subsidy operates at a macro level on NBN Co’s books. To the extent that NBN Co’s topline reported revenue cover its costs and a bit more, that extra money forms the cross-subsidy.

In other words, the cross-subsidy is a consequence of NBN Co’s revenue performance. Who does and doesn’t pay it isn’t governed by any formal rule. It’s just assumed that those who pay it will mostly be in metro areas, where NBN Co’s rollout costs are likely to be least expensive (increasing the likelihood those connections will be profitable).

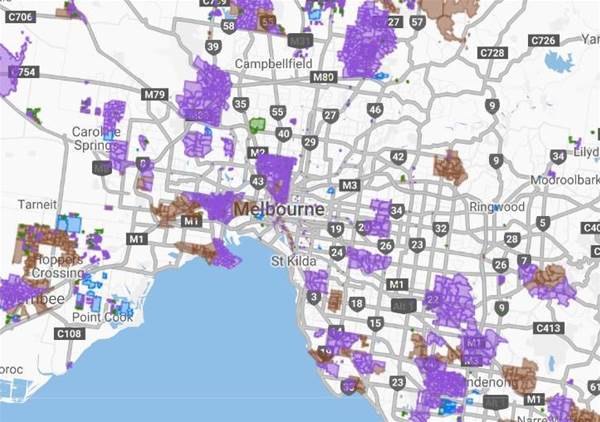

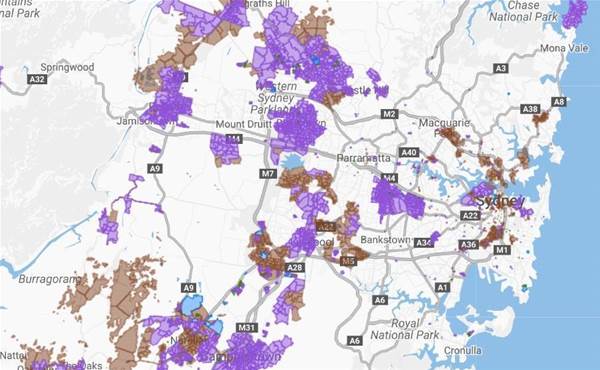

However, iTnews’ reconstruction of the three-year plan - and indeed a cursory glance at any capital city on NBN Co’s rollout map - raises an important issue.

NBN Co’s network footprint in most capital cities is fairly sparse. (Look no further than the available (purple) connections in Melbourne and Sydney-)

CEO Bill Morrow confirmed this in January when he noted that “more than 70 percent of NBN’s rollout has happened in regional and rural areas”. (Actually, the split is more likely around 80/20, based on recent ACCC figures).

This is no accident; former Prime Minister Julia Gillard cut a deal back in 2010 to prioritise the regional and rural rollout in return for the support of key independents.

However, if metro users - those deemed most likely to pay the cross-subsidy of non-metro connections - aren’t able to connect to the network, they also can’t contribute anything to the cross-subsidy.

This is not an issue with the cross-subsidy. It’s an issue with the rollout strategy, and one that has been some seven years in the making.

It isn’t clear what effect bringing more metro users onto the NBN would have on the cross-subsidy. But there is arguably a case to retain it to find out, and give it a chance to succeed.

One of the other puzzling aspects of the proposed ‘broadband tax’ is whether the difference it makes will even be recognisable.

The $7.09 per month tax on any line theoretically capable of speeds of 25Mbps or more would be levied on NBN Co’s customers as well as those with private sector operators like TPG.

It’s unknown how the proposed tax amount varies from the average cross-subsidy, as this is redacted in the government’s explanatory notes.

However, the government has made it clear than NBN Co’s customers would still be responsible for 95 percent of the tax; only five percent of all tax collected would come from the private sector.

The Bureau of Communications Research estimates roughly 380,000 non-NBN line users could find themselves paying the tax by 2022; at today’s tax rate, that would offset NBN Co’s problems by around $2.7 million a month.

The government argues that the tax is needed to enable NBN Co to drop its metro prices to compete for high-value connections, without affecting its ability to subsidise the “non commercial” parts of its network.

“While NBN Co is able to reduce its prices in commercially viable areas to respond to competition if it does so, it will be less capable of supporting cross subsidies to fixed wireless and satellite services,” the government said in a regulatory impact statement (RIS) late last year.

What’s unclear is the degree to which the tax would offset this. The same RIS states that TPG sells 100Mbps NBN services for $100 a month, while its subsidiary Wondercom offers an “identical service” over TPG’s network for “approximately $70”.

It is questionable how much a tax of $7.09 a month would close this price gap. In addition, it is questionable whether replacing the cross-subsidy with a scheme where NBN Co is still responsible for 95 percent of the cost would alleviate the kinds of future shortfalls in the cross-subsidy that the government believes are possible.

A spokesperson for Communications Minister Mitch Fifield did not answer detailed questions filed by iTnews.

Instead, they sought to justify the need for the tax by reiterating some of the reasoning laid out in the RIS and other explanatory documents.

“Consistent with the government's telecommunications regulatory structure and reform policy paper, the regional broadband scheme is designed to establish a long-term funding mechanism for non-commercial services which is transparent and adaptable to changes in the market,” the spokesperson said.

“The [tax] will support regional and remote Australia by ensuring that non-commercial services are adequately funded in the long-term.”

_(20).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

.png&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(28).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Benchmark Awards 2026

iTnews Benchmark Awards 2026

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

The 2026 iAwards

The 2026 iAwards

_(1).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)