The virtual buttons on touchscreens (aka soft keys) enable the wide range of functionality of touchscreen devices - the only downside is that if you can’t see them, they’re next to impossible to use.

The issue led a lengthy court case between Blind Citizens Australia and the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) over the bank’s touchscreen Albert terminals, which left many vision impaired customers being forced to divulge PINs to checkout staff in order to make an eftpos or credit card payment.

Although CBA has since undertaken to provide enhanced accessibility features to its Albert tablets, and offer training to merchants, it doesn’t really solve the problem that touchscreens and other devices without tactile buttons are largely unusable to blind people.

Now a computer science researcher at the University of Sydney, Dr Anusga Withana, is exploring how “blended interfaces, meaning technology that can be worn without being noticed,” might overcome the issue through haptic feedback and the stimulation of different sensations on the fingertips.

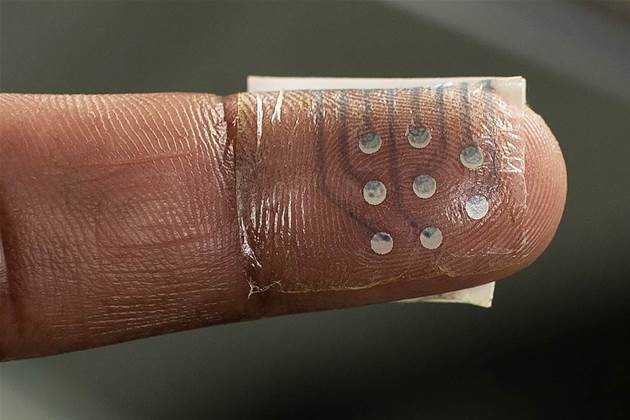

Working with colleagues at Sydney Uni, Monash University and Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Informatics, Withana is developing a printable electronic device called a ‘tacttoo’, that can be temporarily applied to the skin and personalised to suit specific needs.

The screen-printed polymer circuits combine with conductive inks to stretch and move with the skin, maintaining contact between the electronics and the skin while still being thin enough to allow a full sense of touch through the polymer.

When mass-produced, the material content of the tactile tattoos would coss less than one cent and result in a sticky tape-like coating less than half the thickness of a human hair.

“We want people to be able to wear it today and remove it tomorrow – and we want people to be able to create it themselves,” Withana said.

“A broader user goal is to allow people with vision impairment to explore graphical information and more fully comprehend objects in museums and parks. This is something we’re looking at with a team from Monash University.”

While ATMs, phones, and even CBA’s Albert all have headphone ports or speakers for conveying information through audio, Withana said many blind people prefer to use their sense of touch instead.

“some vision-impaired people prefer not to have information come to them through sound, because that’s their connection with the world. If information can come to them in a tactile way, that’s better.”

Blind Citizens Australia agrees, saying that Albert’s previous accessibility features, or lack thereof, “seriously risks its customers’ financial independence, privacy and dignity”.

Down the track, Withana hopes to expand the tacttoo to a more personalised tool, which can be applied to a number of other applications.

Possible uses include sensing an object’s texture or temperature through a prosthetic hand, or gauging the pressure a stroke patient applies to an object to monitor their progress and give them feedback.

.png&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(33).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(28).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

iTnews Benchmark Awards 2026

iTnews Benchmark Awards 2026

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

The 2026 iAwards

The 2026 iAwards

_(1).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)