Earlier this month a group of researchers at MIT’s media lab unveiled an application called Immersion that got people talking about the volume and type of data citizens are readily providing to spy agencies.

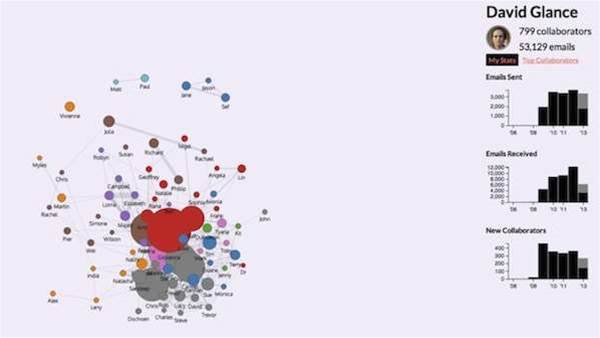

The application uses your email to display all of the people you communicate with in a highly visual way. Although MIT’s Immersion application was designed primarily as a way of illustrating a person’s connections and social networks, it has served to highlight the amount of information that is encoded in communication metadata and what can be done with that data alone, without needing the actual content of emails.

On its own, metadata may not be particularly interesting, especially if, as in my case, it is one of 53,129 emails that is in my work Gmail account. But when visualised using a social network graph, relationships with particular people emerge, along with their place in particular networks. Relationships emerge from the metadata that reflect working structures, particular projects I have worked on and companies that I have interacted with.

The social network graph becomes even more revealing when combined with the email metadata from everyone in the social graph. Now friends of friends become visible and connections between individuals’ social networks show how distant they are from each other.

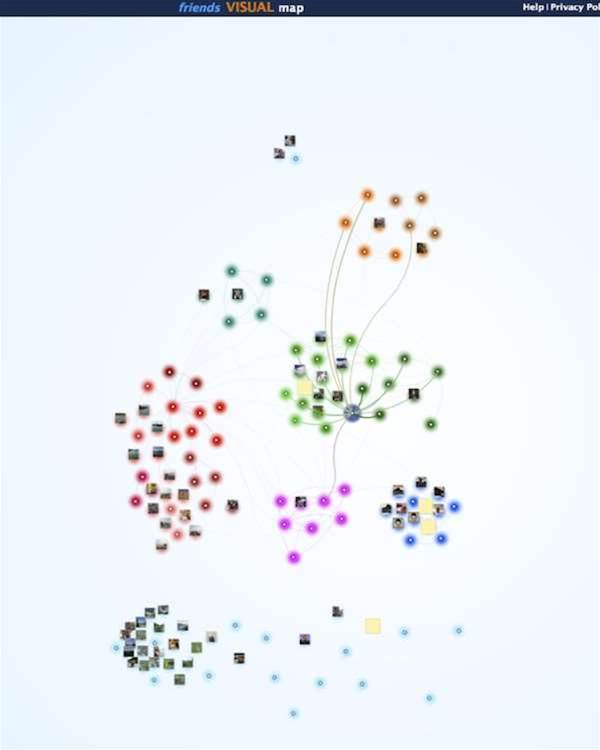

You can see this visualised using another tool called the Challenger Network Graph that takes Facebook data and produces its own social network diagram. Unlike email, Facebook metadata contains much more detailed information about relationships between people. It is after all, designed exactly to do this. Consequently the metadata is even more revealing than email in terms of showing the strengths of connections between individuals and groups.

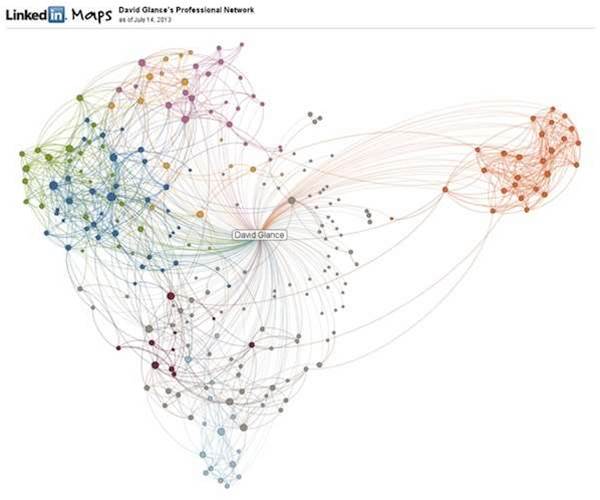

You can also visualise your social network graph on LinkedIn using an application called InMaps. As before, this graph is likely to highlight relationships from places of work but will also show customers and other social connections.

Aggregating all of this information gives a wealth of information and highlights the power of having large amounts of small bits of information. For the public, who are now only slowly becoming aware of the concepts of metadata and what it can reveal, this is an important step in understanding how it underlies our privacy on the internet.

For organisations and countries, the consequences of other countries or organisations having access to this data also comes to the surface. It goes beyond just having access to information about potential terrorists. Simple techniques like social network analysis can reveal important information about corporate and political activity.

Many people claim that as long as an organisation is not looking at the “content” of communications, it is not doing anything wrong. The point however is that you actually don’t need the content to reveal the full extent of what is going on. Encrypting emails may make the senders and receivers believe that their communication is safe, but the mere fact that a communication is encrypted will make that communication stand out and highlight a peculiarity in that relationship. It is in and of itself another important bit of metadata that acts as telltale to the relationship and the connections linking others to it.

Of course, metadata is not confined to email and social networks. There is a wealth of information that users leave behind on every interaction with the internet. Increasingly, this information is also stored in the cloud and the information may at first glance not necessarily seem significant. Hash tags used to search and organise email and Twitter for example can also give information about a person’s interests and connections. More directly, bookmarked URLs and QR codes used to navigate to particular sites also provide information about interests and, in the case of QR codes, location information.

There is really not very much people can do to protect the digital traces left by metadata short of not communicating electronically in the first place. Everything we do electronically leaks information through metadata, most of it hidden from its originators. The fact that the Russian security services are resorting to manual typewriters, paper and presumably microfiche is a testament to the understanding that anything that is electronic is vulnerable to being leaked or leaking information.

_(22).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(28).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(23).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(26).jpg&w=100&c=1&s=0)

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

_(1).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)