Robots might make cars and flip burgers, but could they find and hand you your car keys from a messy desk or bedroom floor?

That question could be answered sooner rather than later as those leading Australia's robotics push forge ahead with efforts to make machines more adaptable to their surroundings.

Robotics researchers at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) have now used a neural network to help robots grasp objects faster and more accurately, even in cluttered and changing environments.

QUT’s Dr Jurgen Leitner said while grasping and picking up an object is a basic task for humans, it’s one that robots struggle with, especially outside of structured settings or when an object is moved.

“The world is not predictable – things change and move and get mixed up and, often, that happens without warning – so robots need to be able to adapt and work in very unstructured environments if we want them to be effective,” Leitner said.

He noted that while robots are currently adapted to “perfectly planned and ordered” settings like factories, this research could mean expanding their use in less structured environments or when greater autonomy is needed.

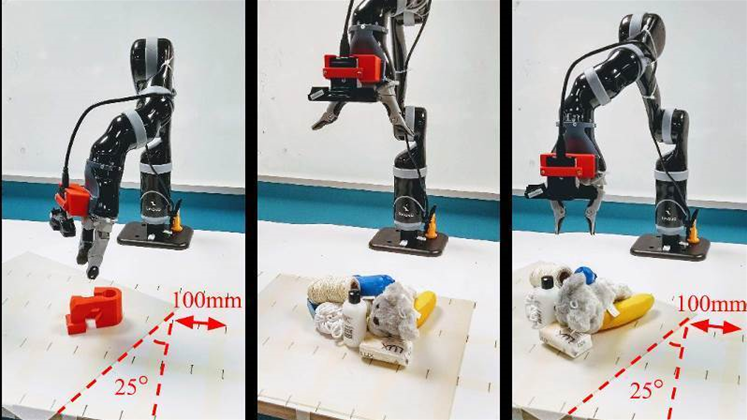

The new method, developed by PhD researcher Douglas Morrison and other QUT researchers, uses a convolutional neural network to process images and model the quality of various grasp poses using a two-fingered mechanism.

The neural network maps the depth of what’s in front of the robot in a single pass and is able to make a decision on the best grasp in around 20 milliseconds, and does so with “greater purpose” even in cluttered spaces, Leitner said.

The neural network is able to follow moving objects and re-adjusts the robot's grasp pose even when the items or surrounding clutter are randomly moved about.

Morrison said the robot had an 83 percent success rate when it was tasked with grasping previously unseen objects with complex geometry, which were moved during the grasp attempt.

Meanwhile common household objects were easier to grasp, with an accuracy of 88 percent, and moving or “dynamic” clutter fared slightly worse with a success rate of 81 percent.

Leitner said the greater robotic flexibility could mean that factories won’t need to be so rigidly laid out in the future.

“It could also be added in the home, as more intelligent robots are developed to not just vacuum or mop a floor, but also to pick items up and put them away,” he added.

The research was supported by the Australian Centre for Robotic Vision which last week launched a national roadmap to guide the greater adoption of robotic technologies across the country.

_(36).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(37).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

Cyber Resilience Summit

Cyber Resilience Summit

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

Huntress + Eftsure Virtual Event -Fighting A New Frontier of Cyber-Fraud: How Leaders Can Work Together

Huntress + Eftsure Virtual Event -Fighting A New Frontier of Cyber-Fraud: How Leaders Can Work Together

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

Melbourne Cloud & Datacenter Convention 2026

Melbourne Cloud & Datacenter Convention 2026

_(1).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)