Amazon is locked in a race against Google to store data on human DNA, seeking both bragging rights in helping scientists make new medical discoveries and market share in a business that may be worth US$1 billion a year by 2018.

Academic institutions and healthcare companies are picking sides between their cloud computing offerings - Google Genomics or Amazon Web Services - spurring the two to one-up each other as they win high-profile genomics business, according to interviews with researchers, industry consultants and analysts.

That growth is being propelled by, among other forces, the push for personalised medicine, which aims to base treatments on a patient's DNA profile. Making that a reality will require enormous quantities of data to reveal how particular genetic profiles respond to different treatments.

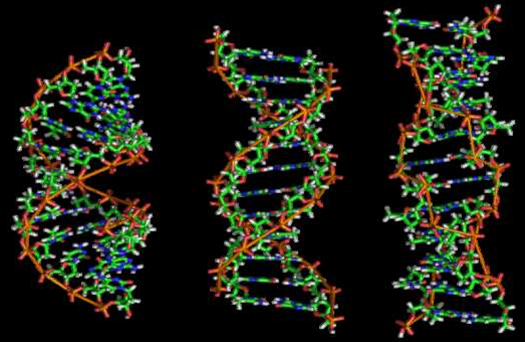

Already, universities and drug manufacturers are embarking on projects to sequence the genomes of hundreds of thousands of people. The human genome is the full complement of DNA, or genetic material, a copy of which is found in nearly every cell of the body.

Clients view Google and Amazon as doing a better job storing genomics data than they can do using their own computers, keeping it secure, controlling costs and allowing it to be easily shared.

The cloud companies are going beyond storage to offer analytical functions that let scientists make sense of DNA data. Microsoft and IBM are also competing for a slice of the market.

Now an estimated US$100 million to US$300 million (A$130 million to A$390 million) business globally, the cloud genomics market is expected to grow to US$1 billion by 2018, said research analyst Daniel Ives of investment bank FBR Capital.

By that time, the entire cloud market should have US$50 billion to US$75 billion in annual revenue, up from about US$30 billion now.

"The cloud is the entire future of this field," said Craig Venter, who led a private effort to sequence the human genome in the 1990s. His new company, San Diego-based Human Longevity, recently tried to import genomic data from servers at the J. Craig Venter Institute in Rockville, Maryland.

The transmission was so slow, scientists had to resort to sending disks and thumb drives by FedEx and human messengers, or "sneakernet," he said. The company now uses Amazon Web Services.

So does a collaboration between Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Pennsylvania-based Geisinger Health Systems to sequence 250,000 genomes. Raw DNA data is uploaded to Amazon's cloud, where software from privately-held DNAnexus assembles the millions of chunks into the full, three-billion-letter long genome.

DNAnexus's algorithms then determine where an individual genome differs from the "reference" human genome, the company’s chief scientist Dr David Shaywitz said, in hopes of identifying new drug targets.

Hosting for free

Showing how important Google and Amazon view this business to be, and how they hope to use existing customers to lure future ones, each is hosting well-known genomics datasets for free.

Neither company discloses the amount of genomics data it holds, but based on interviews with analysts and genomic scientists, as well as the companies' own announcements of customers they’ve won, Amazon Web Services slice may be bigger.

Data from the "1000 Genomes Project," an international public-private effort that identified genetic variations found in at least one percent of humans, reside at both Amazon and Google "without charge" said Kathy Cravedi of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), one of the project's sponsors.

Other paying clients with a more specific focus are picking sides.

Google, for instance, won a project from the Autism Speaks foundation to collect and analyse the genomes of 10,000 affected children and their parents for clues to the genetic basis of autism.

Another customer is Tute Genomics, whose database of 8.5 billion human DNA variants can be searched for how frequently any given variant appears, what traits it's associated with and how people with a certain variant respond to particular drugs.

Amazon is hosting the Multiple Myeloma Foundation’s project to collect complete-genome sequences and other data from 1000 patients to identify new drug targets. It also won the Alzheimer's Disease Sequencing Project, which has similar aims.

Amazon charges about US$4 to US$5 a month to store one full human genome, and Google about US$3 to US$5 a month. The companies also charge for data transfers or computing time, as when scientists run analytical software on stored data.

Amazon's database-analysis tool, Redshift, costs US$0.25 (A$0.32) an hour or US$1000 per terabyte per year, the company said.

Genetic gold

Another part of the cloud services' pitch to would-be customers is that their analytic tools can fish out genetic gold - a drug target, say, or a DNA variant that strongly predicts disease risk - from a sea of data. Any discoveries made through such searches belong to the owners of the data.

"On the local university server it might take months to run a computationally-intense" analysis, said Alzheimer’s project leader Dr Gerard Schellenberg of the University of Pennsylvania. "On Amazon, it's, 'how fast do you need it done?', and they do it."

Another selling point is security. Universities are "generally pretty porous," said Ryan Permeh, chief scientist at cybersecurity company Cylance, and the security of federal government computers is "not at the top of the class".

While academic and pharmaceutical research projects are the biggest customers for genomics cloud services, they will be overtaken by clinical applications in the next ten years, said Google Genomics director of engineering David Glazer.

Individual doctors will regularly access a cloud service to understand how a patient's genetic profile affects his risk of various diseases or his likely response to medication.

"We are at that transition point now," Glazer said.

Matt Wood, general manager for Data Science at Amazon Web Services, sees cloud demand in genomics now as "a perfect storm," as the amount of data being created, the need for collaboration and the move of genomics into clinical care accelerate.

Experts on DNA and data say without access to the cloud, modern genomics would grind to a halt.

Bioinformatics expert Dr Atul Butte of the University of California, San Francisco, said that now, when researchers at different universities are jointly working on NIH and other genomic data, they don't have to figure out how to make their computers talk to each other. In March, NIH cleared the way for major research on the cloud when it began allowing scientists to upload important genomic data.

"My response was: it's about time," Butte said.

_(36).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

Cyber Resilience Summit

Cyber Resilience Summit

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

Huntress + Eftsure Virtual Event -Fighting A New Frontier of Cyber-Fraud: How Leaders Can Work Together

Huntress + Eftsure Virtual Event -Fighting A New Frontier of Cyber-Fraud: How Leaders Can Work Together

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

Live & Hands On Demo: Navigating the BMC AMI DevX Platform to Understand Code Faster Using AI

Live & Hands On Demo: Navigating the BMC AMI DevX Platform to Understand Code Faster Using AI

_(1).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)