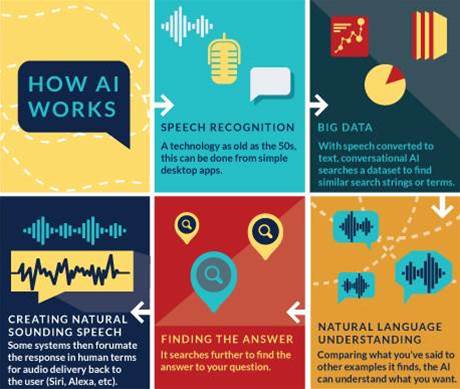

With the spread of online customer service chatbots, and Apple, Amazon, and Google's voice services, we're getting used to conversational AI: software that understands us, talks back, and solves our problems. But where can the field go from here, and what else can it do?

When it comes to resources, the sky's the limit. As most of the components of conversational AI live and work in the cloud, they have ever-increasing datasets and processing to draw on, and that will mean more responsive results that can act in more expanded fields of enquiry.

And as the backend grows to comprise more information that can help AI learn, the interface at the user end – often as simple as a chat window or spoken command – need give no indication of the massive amount of parallel processing going on behind the scenes to put an answer together.

The trick with AI is that human language is infinitely variable, and you can't hard code it.

"The amount of work involved in trying to predict what people will say, every alternative way they could say every sentence, and every sequence of thought they'll take to get something done, is simply way too vast even for an army of Googlers," is how Rollo Carpenter, creator of Cleverbot, puts it.

One of the problems is we're a little bit conditioned by pop culture into thinking a conversational AI agent should be like C-3PO or the synthetic humans from the Alien franchise - extremely general assistants whose spoken interactions are almost indistinguishable from another human.

Instead, most AI scientists will tell you conversational AI will work better in more specialised cases, drawing from a smaller but more accurate dataset within a given domain.

Most of us are used to the 'wide and shallow' use case for conversational AI, like asking Google to find cat videos, but the current state of the technology is more about 'deep and narrow' use.

An example is a system that crunches mining survey data, programmed to pinpoint where mineral deposits will likely be because it understands the formation of crystals, tectonic stress and the cost/benefit economics of digging. Ask it to find a cat video or tell you tomorrow's weather and it'll flounder.

In fact, even the language we ourselves use to talk to conversational AI will vary depending on the domain, and applications today are being built to understand human speech in specialist areas like law, engineering and customer service.

It's similar to when you talk to speech recognition software on your PC, letting it get used to the spelling of words and context of terms and phrases particular to your industry, albeit on a much grander scale.

Tim Tuttle, founder and CEO of conversational AI software provider MindMeld, says such deeper, narrower domains of expertise are the name of the game in the industry right now.

He points to market leaders like Siri and Amazon Echo, noting that they deal with specific domaisn like movie sessions times, calendar appointments, and home automation.

"There's no general purpose universal natural language understanding today," he says.

"Even though the technology will be capable of supporting that in the near future, it isn't yet."

More than words

Of course, there's a lot more in human communication than just words. In 1971 a psychologist minted the 7-38-55 rule – percentages of the relative impact of words, tone of voice and body language when speaking.

Today conversational AI researchers are building computers that can take the emotional cadence of spoken conversation into account.

One is Watson, the system from IBM made famous when it beat two human players at the game show Jeopardy in 2011. Watson's CTO and vice president, IBM fellow Rob High, says some of Watson's current programming includes emotional intelligence to help the user progress through what he calls a positive emotional arc.

"Detecting the tone of the user is key to emotional intelligence so a conversation is appropriate to all types of customer queries, even angry situations," High says.

"The goal of every conversation is to leave the user satisfied and feeling inspired, and we see emotional intelligence and deep reasoning as the next frontiers for virtual assistants."

Watson already has a raft of modules that can analyse text for emotion, tone and personality. The company says its Watson Natural Language Understanding product can distinguish between joy, fear, sadness, disgust, and anger, among others.

But High says the engineers and programmers at Watson are interested in something ever deeper, often thought of as the holy grail of conversational AI. Where we humans are uniquely built to adapt and change focus to a new topic and understand new context quickly, getting a computer to do the same is far more cumbersome.

And having a computer understand what you really want to know – even aside from what you actually say – is the next frontier.

"A lot of chatbots only focus on command/response, like 'what's my account balance?'," High says, "but I think that misses the point. Knowing your account balance isn't the problem, the real problem for the user is ... they're getting ready to buy something, saving for college, re-balancing their investments."

Starting with what might be a very innocuous initial query, High says the system should then shepherd the user through the process, offering other points of view and inspiration if necessary.

James Canton, a long-standing futurist with a focus on technology, goes one step further. He believes that when we give conversational AI the equivalent of other senses, the results will be even better.

"AI needs senses like vision to see and interact; some smart optics would enhance AI and be very useful, so would a larger sensor network that's both GPS and IoT ready. Future tech like quantum computing and neuromorphic chips will accelerate [it further]."

But when it comes to understanding the context of a conversation, there's still plenty a computer can learn from mere text, according to Cleverbot's Carpenter.

He says that unlike almost every other conversation system, Cleverbot agents use deep context to decide how to respond next, looking back 50 lines into the current conversation before every response and comparing them past conversations.

"It's only because of that deep context that it's at all possible for it to hold conversations like it," he says.

Read on to find out how close we are to truly conversational AI

_(23).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(22).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(26).jpg&w=100&c=1&s=0)

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

_(1).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)