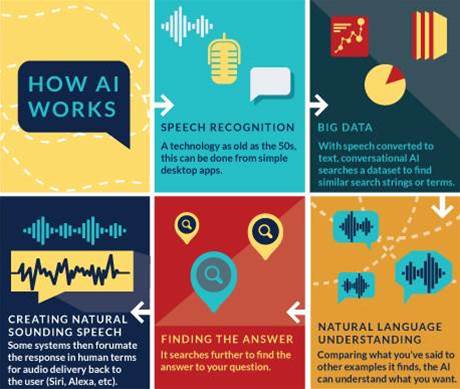

With the spread of online customer service chatbots, and Apple, Amazon, and Google's voice services, we're getting used to conversational AI: software that understands us, talks back, and solves our problems. But where can the field go from here, and what else can it do?

When it comes to resources, the sky's the limit. As most of the components of conversational AI live and work in the cloud, they have ever-increasing datasets and processing to draw on, and that will mean more responsive results that can act in more expanded fields of enquiry.

And as the backend grows to comprise more information that can help AI learn, the interface at the user end – often as simple as a chat window or spoken command – need give no indication of the massive amount of parallel processing going on behind the scenes to put an answer together.

The trick with AI is that human language is infinitely variable, and you can't hard code it.

"The amount of work involved in trying to predict what people will say, every alternative way they could say every sentence, and every sequence of thought they'll take to get something done, is simply way too vast even for an army of Googlers," is how Rollo Carpenter, creator of Cleverbot, puts it.

One of the problems is we're a little bit conditioned by pop culture into thinking a conversational AI agent should be like C-3PO or the synthetic humans from the Alien franchise - extremely general assistants whose spoken interactions are almost indistinguishable from another human.

Instead, most AI scientists will tell you conversational AI will work better in more specialised cases, drawing from a smaller but more accurate dataset within a given domain.

Most of us are used to the 'wide and shallow' use case for conversational AI, like asking Google to find cat videos, but the current state of the technology is more about 'deep and narrow' use.

An example is a system that crunches mining survey data, programmed to pinpoint where mineral deposits will likely be because it understands the formation of crystals, tectonic stress and the cost/benefit economics of digging. Ask it to find a cat video or tell you tomorrow's weather and it'll flounder.

In fact, even the language we ourselves use to talk to conversational AI will vary depending on the domain, and applications today are being built to understand human speech in specialist areas like law, engineering and customer service.

It's similar to when you talk to speech recognition software on your PC, letting it get used to the spelling of words and context of terms and phrases particular to your industry, albeit on a much grander scale.

Tim Tuttle, founder and CEO of conversational AI software provider MindMeld, says such deeper, narrower domains of expertise are the name of the game in the industry right now.

He points to market leaders like Siri and Amazon Echo, noting that they deal with specific domaisn like movie sessions times, calendar appointments, and home automation.

"There's no general purpose universal natural language understanding today," he says.

"Even though the technology will be capable of supporting that in the near future, it isn't yet."

More than words

Of course, there's a lot more in human communication than just words. In 1971 a psychologist minted the 7-38-55 rule – percentages of the relative impact of words, tone of voice and body language when speaking.

Today conversational AI researchers are building computers that can take the emotional cadence of spoken conversation into account.

One is Watson, the system from IBM made famous when it beat two human players at the game show Jeopardy in 2011. Watson's CTO and vice president, IBM fellow Rob High, says some of Watson's current programming includes emotional intelligence to help the user progress through what he calls a positive emotional arc.

"Detecting the tone of the user is key to emotional intelligence so a conversation is appropriate to all types of customer queries, even angry situations," High says.

"The goal of every conversation is to leave the user satisfied and feeling inspired, and we see emotional intelligence and deep reasoning as the next frontiers for virtual assistants."

Watson already has a raft of modules that can analyse text for emotion, tone and personality. The company says its Watson Natural Language Understanding product can distinguish between joy, fear, sadness, disgust, and anger, among others.

But High says the engineers and programmers at Watson are interested in something ever deeper, often thought of as the holy grail of conversational AI. Where we humans are uniquely built to adapt and change focus to a new topic and understand new context quickly, getting a computer to do the same is far more cumbersome.

And having a computer understand what you really want to know – even aside from what you actually say – is the next frontier.

"A lot of chatbots only focus on command/response, like 'what's my account balance?'," High says, "but I think that misses the point. Knowing your account balance isn't the problem, the real problem for the user is ... they're getting ready to buy something, saving for college, re-balancing their investments."

Starting with what might be a very innocuous initial query, High says the system should then shepherd the user through the process, offering other points of view and inspiration if necessary.

James Canton, a long-standing futurist with a focus on technology, goes one step further. He believes that when we give conversational AI the equivalent of other senses, the results will be even better.

"AI needs senses like vision to see and interact; some smart optics would enhance AI and be very useful, so would a larger sensor network that's both GPS and IoT ready. Future tech like quantum computing and neuromorphic chips will accelerate [it further]."

But when it comes to understanding the context of a conversation, there's still plenty a computer can learn from mere text, according to Cleverbot's Carpenter.

He says that unlike almost every other conversation system, Cleverbot agents use deep context to decide how to respond next, looking back 50 lines into the current conversation before every response and comparing them past conversations.

"It's only because of that deep context that it's at all possible for it to hold conversations like it," he says.

Read on to find out how close we are to truly conversational AI

Tomorrow's AI helpers, today

That might all be well and good, but honestly, we all really want general conversational AI agents.

When we plug one into a humanoid robot we'll finally live in a world containing all those awesome robots we've seen in movies and comic books.

Surely such a system can't be too far off? After all, Watson had to wield very generalist knowledge to win at Jeopardy. Not only did it have to understand the question (which is in the form of an answer), it had to do the reasoning about a response, put it in the appropriate terms (which is in the form of a question), and do it all inside three seconds to be competitive enough to beat its human opponents.

Watson's Rob High says IBM researchers recently combined deep learning techniques with acoustic and language models to reach what he calls a 'record milestone in automatic speech recognition'.

It brought the word error rate down to 5.5 percent accuracy (and if someone says 'I absolutely went to town' and you say 'really, did you drive or catch the train?' and blush as everyone laughs, you'll know human communication is far from 100 percent accurate).

James Canton thinks ubiquitous general conversational AI will be with us in two to five years, or sooner.

Carpenter thinks we'll be conversing with machines as if they're intelligent within 10 years.

He says an approach Cleverbot takes (in a quite human-like gesture) is to accept that it can't be perfect – to say inaccurate, humorous or crazy-seeming things in parts of the 'infinite conversational space' and to learn what people really want to talk about.

"A huge amount of data can be gathered that not only means it constantly improves now, while entertaining people, but will be used all the more with computing power and machine learning techniques in the future," he says.

There's just one stumbling block, as Carpenter sees it.

"The goalposts are constantly moving. As we get used to what machines are currently capable of, we adjust our interpretation of what is really intelligent and human."

The real conversational AI

But as cool as it would be for science fiction geeks and housework, is such human-like, general knowledge conversational AI even something we should be aiming for?

"There's not a lot of value in replicating the human mind into a computer," says Rob High.

"The human brain is incredibly complex and there's still a lot of work to be done to understand fully how it works. We're not trying to replicate the human mind in cognitive computing, we're trying to figure out what humans are good at and not good at and how to fill in the gaps - how to extend human cognitive reach."

To High, that means conversational AI and the systems that underpin it need to understand what the human user intends, reason about his or her problem in a way that draws conclusions, and learn so it can improve its understanding and reasoning over time.

Tim Tuttle agrees, predicting conversational AI won't supplant human communication as much as take out some of the grunt work.

"With truly conversational AI users will be able to interact with their devices in a way that streamlines common daily tasks like placing an order at a restaurant, booking a flight or hotel, or creating a service appointment at a doctor's office."

Employment shock

You can't talk about any kind of machine learning technology today without acknowledging the potential threat to jobs, and as conversational AI gets better, it will likewise have an effect.

As Cleverbot's Rollo Carpenter says; "AI overall is certainly going to be economically transformative. Some [changes] will be enormously positive even while disrupting vested interests. We're all going to have to adjust, and the role of government will need to evolve too."

He agrees some work – like repetitive call centre customer service – will surely be taken over by AI, but says the need for human oversight and interjection into more complicated problems and queries will be around for a long time, and there might even be more of it than what's lost or replaced by conversational AI.

"When machines are able to talk naturally, genuinely understanding not only language but also needs, people will talk a lot more, whether to companies' bot representatives or virtual individuals," Carpenter says.

"Much more conversation will happen overall because it will be good or very useful conversation. Right now people avoid calling helplines because they know it'll be a nightmare."

Technology futurist James Canton believes the co-evolution of AI and humans will mean some work will be collaborative and some will be competitive, but that there are some things robots or AI can never do.

"I don't want a robotics massage or lover," he says, "but robots will replace many jobs generating income for a new autonomous economy that will benefit humanity."

_(28).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(23).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

.png&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(26).jpg&w=100&c=1&s=0)

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

_(1).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)