It's December, the year's drawing to a close, and I'm going to dedicate this column to the the topic of Heartbleed, the highly publicised vulnerability in the popular OpenSSL cryptographic library.

"What else is there to say about Heartbleed? Surely everyone's patched by now," I hear you say.

That's a perfectly reasonable thing to say, but allow me to disabuse readers of that notion, because there are lots of systems out there which first made headlines a full eight months ago that remain vulnerable to Heartbleed.

In fact, the Shodan search engine for internet-connected devices throws up 308,885 results when you look for Heartbleed.

Most of the Heartbleed hits come from the United States, with Germany in second place followed by France, Russia and the UK.

Shodan lists the organisation with the most vulnerable systems as Amazon and, oh boy, there are lots of unpatched Apache web servers out there.

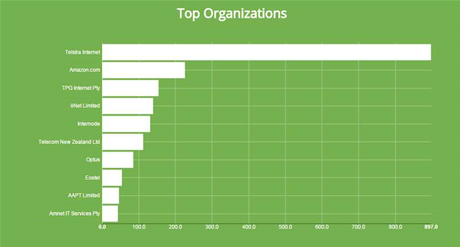

In Australia and New Zealand there are plenty of Heartbleed vulnerable systems - 3017 here and 651 across the Tasman.

Source: Shodan

Telstra appears to be the organisation and domain with the most systems vulnerable to Heartbleed, followed by Amazon. I would hazard a guess that this is possibly is due to hosted machines, real and virtual, that aren't being updated.

Shodan also picked up two South Australian government web servers that ought to be patched quite urgently.

Source: Shodan

The large amount of vulnerable systems surprised John Matherly, the founder of Shodan.

"I did expect there to be fewer vulnerable devices, if nothing else due to regular system updates," Matherly told iTnews.

Heartbleed was the first vulnerability to be neatly branded and marketed, and as a result there was plenty of coverage outside tech circles, Matherly noted. But not enough coverage to expunge the problem.

"I would've expected management to also be more vocal about making sure that their IT department patched all affected devices. But apparently that wasn't the case and Heartbleed remains a large factor on the internet," he said.

Matherly thought the publicity would explain why it was important to patch against Heartbleed - and at this stage, it's worth recapitulating that the flaw in vulnerable versions of OpenSSL is very easy to exploit without being noticed.

Furthermore, the patch isn't very invasive. It has received a huge amount of scrutiny by a large field of techies ranging from security people to systems administrators, and should be of high quality.

So why are there still so many vulnerable systems out there?

One explanation I came across was that "if it's not too obviously broken, don't risk your job trying to fix it". In other words, admins having been burnt in the past with bad quality updates don't trust the patches they are provided.

Things can go wrong and when they do, don't expect anyone to understand why or show any sympathy.

Matherly agreed.

"In general, you're right in that security doesn't make money for a company. It can be a tough call to fix something that's working and risk downtime (which can result in a company losing money), or just keep going until something actually breaks," he said.

I'd be interested to hear what reasons (or excuses) there are for leaving such a large amount of systems basically wide-open to full exploitation. In the meantime, it's handy for us to have the likes of Shodan to keep track of them.

Handy for the hackers too, don’t forget.

_(37).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

Cyber Resilience Summit

Cyber Resilience Summit

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

Huntress + Eftsure Virtual Event -Fighting A New Frontier of Cyber-Fraud: How Leaders Can Work Together

Huntress + Eftsure Virtual Event -Fighting A New Frontier of Cyber-Fraud: How Leaders Can Work Together

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

Melbourne Cloud & Datacenter Convention 2026

Melbourne Cloud & Datacenter Convention 2026

_(1).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)