In less than two days ransomware derived from leaked NSA exploits has spread across the globe to infect hundreds of thousands of PCs at critical operations like hospitals, schools and telcos.

Britain and Russia were the worst hit, but the WannaCrypt/WannaCry ransomware has so far attacked 200,000 victims across 150 countries.

For now, the ransomware outbreak has been somewhat contained thanks to a UK researcher who managed to accidentally shut the operation down by simply registering a domain.

But security experts say the threat is far from over.

Europol has warned of an escalating threat as employees return to work on Monday and boot their Windows PCs.

In Australia - which has largely escaped damage - two more reports emerged on Monday morning of organisations falling victim. It brings the total number to three.

The federal government has declined to name the three victim organisations, but said they were small-to-medium sized operations.

Update 6pm: The federal government has advised the total victim count has now risen to eight.

The Australian Cyber Security Centre has warned local organisations that the ransomware is "highly likely to impact Australian government, industry, and individuals”.

It urged those affected to contact the ACSC on 1300 CYBER1.

What is WannaCrypt/ WannaCry?

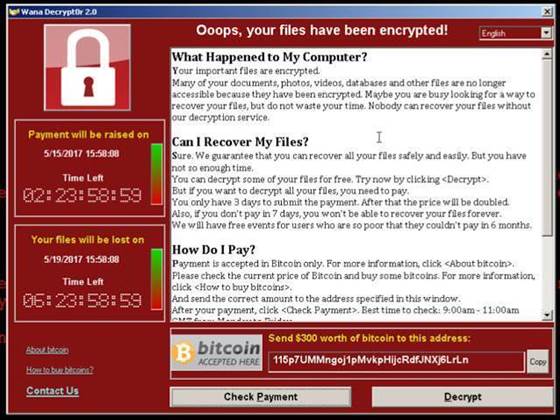

WannaCrypt/WannaCry is a type of ransomware that attempts to render a computer unusable by encrypting the files on the system.

Victims are then asked to pay a ransom to unscramble their files.

The current WannaCrypt variant initially asks for US$300 and then later doubles to US$600, before threatening to delete files completely if the victim doesn't pay up within a week.

So far the attackers appear to have made around US$18,000 in Bitcoin payments from around 52 victims.

How does it work?

The malware spreads through the Windows Server Message Block (SMB) v1 file sharing protocol. It is self-replicating, so propagates the infection to other computers that respond to SMBv1 requests.

Because it spreads via SMB it means even computers behind firewalls can be affected.

It uses two leaked exploits linked to the US National Security Agency, codenamed ETERNALBLUE and DOUBLEPULSAR.

The ETERNALBLUE module allows for the initial exploitation of the SMBv1 flaw, and then the DOUBLEPULSAR backdoor is implanted to allow the attacker to install the malware.

According to Talos, the ransomware checks for disk drives, "including network shares and removable storage devices mapped to a letter, such as 'C:/', 'D:/' etc", and then checks files with a file extension of certain names.

It then encrypts everything it finds using 2048-bit RSA encryption.

How was it contained?

A UK security researcher managed to contain the ransomware simply by registering a domain for US$10.69.

After obtaining a sample of the malware, the researcher going by the name MalwareTech discovered that it queried an unregistered domain. So he registered it, inadvertently stopping the spread of the ransomware.

It turns out the ransomware made requests to the domain - iuqerfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea.com - and if the connection was not successful, it ransomed the system.

If successful, however, the malware exits, leading MalwareTech to believe the domain is a "kill switch" in case something goes wrong.

However many security researchers now believe it was not a kill switch, rather an effort to stop others reverse engineering the malware's code.

Although this sinkholing of the malware has stopped the rate of infection for now, MalwareTech warned it may only be a temporary fix. He expects the ransomware's authors, or others seeking similar levels of destruction, to release a new variant with modified code.

What can I do to protect myself?

Patch. Now.

Security experts expect that the number of infections - which currently sits at around 200,000 - will rise this week as workers return to offices and boot their unpatched Windows PCs.

Additionally, the sinkholing of the domain won't work for those who use proxy servers between their networks and the internet, according to security researcher Didier Stevens.

The best bet is to make sure your systems are fully patched and that you have a strong back-up strategy in place to mitigate any loss or destruction of files.

Microsoft issued a "highly unusual" security patch for the out-of-support Windows XP, Windows 8, and Windows Server 2003 operating systems over the weekend to fix the holes in SMBv1.

It had issued a patch for the flaws - which were detailed in the Shadow Brokers leak of the exploits earlier this year - for its supported systems in March.

Windows 10 machines don't contain this vulnerability and therefore aren't susceptible to the ransomware spreading through its current method, Microsoft has said.

But organisations running any version of Windows older than Windows 10 need to ensure their systems are fully patched.

Security researcher Troy Hunt also recommends making sure SMB ports (139,445) are blocked from all externally accessible hosts.

If your organisation is struggling to implement the patch, consider disabling SMBv1 altogether while you work on getting your systems secured.

.png&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

.png&w=120&c=1&s=0) Tech in Gov 2025

Tech in Gov 2025

Forrester's Technology & Innovation Summit APAC 2025

Forrester's Technology & Innovation Summit APAC 2025

.png&w=120&c=1&s=0) Security Exhibition & Conference 2025

Security Exhibition & Conference 2025

Integrate Expo 2025

Integrate Expo 2025

Digital As Usual Cybersecurity Roadshow: Brisbane edition

Digital As Usual Cybersecurity Roadshow: Brisbane edition

.jpg&h=271&w=480&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)