An encryption algorithm for securing voice and messaging over the internet, developed and promoted by the British government, has been found to contain a backdoor that gives full access to protected communications.

Known as MIKEY-SAKKE, the cryptographic algorithm was developed by a division of Britain's Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) spy agency.

It was proposed as an open Internet Enginering Task Force (IETF) standard in 2012, and promoted as having a "number of desirable features, including simplex transmission, scalability, low-latency call setup, and support for secure deferred delivery".

The crypto algorithm forms part of the UK government's encryption guidance for securing communications over the internet, but a University College of London (UCL) researcher this week published a report showing the protocol comes with an backdoor, allowing undetectable access for anyone with a master key.

Far from enabling secure communications, Dr Steven Murdoch of the UCL Information Security Research Group noted MIKEY-SAKKE was designed with "a desire to allow undetectable and unauditable mass surveillance."

"... in the vast majority of cases the properties that MIKEY-SAKKE offers are actively harmful for security. It creates a vulnerable single point of failure, which would require huge effort, skill and cost to secure – requiring resource beyond the capability of most companies," Murdoch wrote.

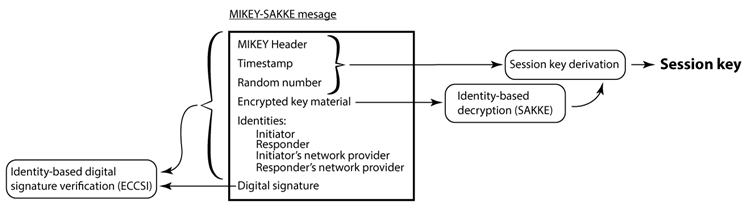

MIKEY-SAKKE has the advantage of not using cumbersome digital certificates, as it uses identity-based encryption for key exchange; this means private keys for users are generated by network providers with a master private key.

These master private keys are valid indefinitely, and make the crypto algorithm vulnerable to silent interception and future decryption, the researcher said.

"The existence of a master private key that can decrypt all calls past and present without detection, on a computer permanently available, creates a huge security risk, and an irresistible target for attackers," Murdoch wrote.

"Also calls which cross different network providers (e.g. between different companies) would be decrypted at a gateway computer, creating another location where calls could be eavesdropped."

In particular, MIKEY-SAKKE supports key escrow, the UCL researcher said. Thanks to the design of the crypto protocol, it is possible to retrieve responder private keys to decrypt past calls, without the parties communicating with one another being able to detect the interception, according to Murdoch.

Prior to Murdoch’s report, a September 2014 memorandum [pdf] circulated at the 3GPP Technical Specification Group, a mobile telco industry forum, made it clear that MIKEY-SAKKE encrypted communications could be eavesdropped upon if needed.

Murdoch likened the MIKEY-SAKKE protocol design to the Clipper encryption device which was promoted by the United States National Security Agency (NSA) in 1993.

Although Clipper only allowed audited government agencies to decrypt communications, it was abandoned due to the inherent risks of keys falling into the wrong hands, and weaknesses in the implementation of the electronic chip itself.

Murdoch said MIKEY-SAKKE contained other weaknesses as well, including that it does not attempt to hide the identity of the users communicating with the protocol - only the content of calls and messages. This makes it possible to map who is using the protocol, and when.

Murdoch suggested using the open source Z Real-time Transport Protocol (ZRTP) that uses Ephmeral Diffie-Hellman key negotiation protocol as a safer alternative, to prevent quiet surveillance of communications by governments and hackers.

ZRTP encrypts communications and keeps them safe from network providers. The protocol also verifies the identity of the parties' communications, and has forward security, meaning past calls cannot be decrypted even if keys are intercepted.

_(36).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

Cyber Resilience Summit

Cyber Resilience Summit

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

Huntress + Eftsure Virtual Event -Fighting A New Frontier of Cyber-Fraud: How Leaders Can Work Together

Huntress + Eftsure Virtual Event -Fighting A New Frontier of Cyber-Fraud: How Leaders Can Work Together

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

Melbourne Cloud & Datacenter Convention 2026

Melbourne Cloud & Datacenter Convention 2026

_(1).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)