Democracy, blessed with an adverserial leadership selection process, is always a bit messy. Sometimes a lot.

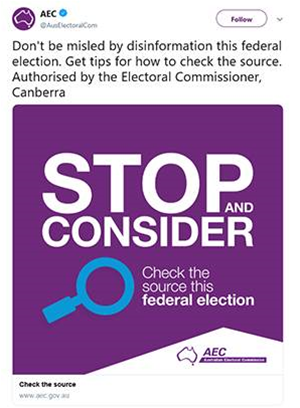

Now, with interference fears at new highs, the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) has launched an online advertising blitz it hopes will prompt voters to “carefully check the source of electoral communication they see or hear over the course of this coming federal election”.

It’s a bold move, but even the custodian of Australia's big isn't completely certain the campaign is necessary. Better out in front than cleaning up from behind it seems.

Dubbed “Stop and Consider”, the online campaign will have the AEC's ads run on “platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram”.

As the campaign’s website points out, “A federal election is a contest of ideas and electoral laws do not regulate the truth of electoral communications.” The Commission therefore points out that “During a federal election there is a large amount of information being distributed, much of it online, which is seeking to influence your vote. Some of this may be disinformation, or false information.”

The Commission appears to worry about that in two dimensions, one of which is that fake news campaigns directed by foreign entities could “disrupt Australian elections through disinformation.”

Electoral Commissioner Tom Rogers said the AEC hasn’t actually seen such campaigns, “but given apparent events in other parts of the world, it was prudent to be vigilant.”

Voters are thus asked to consider whether election-related stuff they see online comes from a reputable source, is recent, and is not a disinformation or scam.

This, of course, differs from locally produced disinformation and dubious claims made by authorised political candidates and their backers here, showing that all politics literally is local.

The other dimension to the AEC's campaign is countering bad information about campaigning and voting, hence Stop and Consider's aim to position the AEC as “The key official source for voters to know what they have to do to participate successfully at this federal election”.

While iTnews asked the AEC how much it intends to spend on the campaign and if it is running it in-house, or through advertising agencies, we hadn't received a response at the time of publication.

That said, ad budgets in government are routinely kept quiet for commercial reasons.

Do platforms even matter?

Not everyone is convinced the voting public are easily duped.

Over at Macquarie University, political scientist Dr Glenn Kefford poured cold water on social media election manipulation fears, using a pithy post to the institution's Lighthouse blog to venture that that political paranoia (cue the Black Sabbath) could be overstated.

"What we know is that digital messaging can have a small but significant effect on mobilisation, that there are concerns about how it could be used to demobilise voters, and that it is an incredibly effective way to fundraise and to organise," Kefford said.

"However, its ability to independently persuade voters to change their vote is estimated to be close to zero."

Although Kefford points out there is still more research needed, politicians flock to social media because that's where the people are and its cheap. Which isn't influence per se, even if it is on-trend.

"The exaggeration and lack of clarity around digital is problematic not just because there is almost no evidence to support many of the claims made, but because this type of technology fetishism implies that voters are easily manipulated, when there is little to suggest this is the case," Kefford said.

"While it might help some commentators rationalise unexpected election results, rather than blaming technology, a more fruitful endeavour would be to try to understand why voters are attracted to various parties or candidates like what happened in the US with Trump."

Astroturf abounds

Of course there can always be completely spontaneous uprisings of common interest around pertinent issues of the day that reflect legitimate viewpoints.

Just take not-for-profit group the International Social Media Association (ISMA) that say's it's "dedicated to harmonising legislation and policies on a global scale" and aims to "advance, protect and balance the rights of businesses and individuals on the digital platforms which are used every day."

There's not a social media brand logo like Facebook, Insta or Twitter anywhere on the group's site and it's stakeholders appear to be mainly lawyers.

The group is deeply critical of recent legislation thumping social media companies with stiff penalties in the wake of the Christchurch shooting massacre that was streamed live by the alleged perpetrator on Facebook.

"This reactionary legislation disproportionately puts sole responsibility on the social media platforms and internet service providers, whilst entirely neglecting to consider the agency and culpability of individual users,” ISMA said in a statement.

"By misguidedly focussing on social media executives, the government has overlooked the real need to educate individual users about the repercussions of their actions online."

There's no interest like self interest.

_(36).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(33).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

Cyber Resilience Summit

Cyber Resilience Summit

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

Huntress + Eftsure Virtual Event -Fighting A New Frontier of Cyber-Fraud: How Leaders Can Work Together

Huntress + Eftsure Virtual Event -Fighting A New Frontier of Cyber-Fraud: How Leaders Can Work Together

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

Melbourne Cloud & Datacenter Convention 2026

Melbourne Cloud & Datacenter Convention 2026

_(1).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)