Banks will be obliged to reveal consumer data about 27 deposit and lending products under planned open banking laws, but will not have to share data they have transformed for analysis purposes.

Treasurer Scott Morrison today released a 158-page review of how an open banking scheme could look in Australia.

Morrison committed to open banking at the last federal budget. It forms part of a broader consumer data right, and allows customers access to certain types of data held by banks.

The review confirms that much of this data may be already available to customers, albeit not in a format that makes it easy to provide to someone else.

It also provides relief for banks by exempting both “value-added” and “aggregated” data sets from the scope of requests.

This will mean data stores where raw data has been transformed or aggregated with other data as part of BI or analytics projects can’t be requested for release.

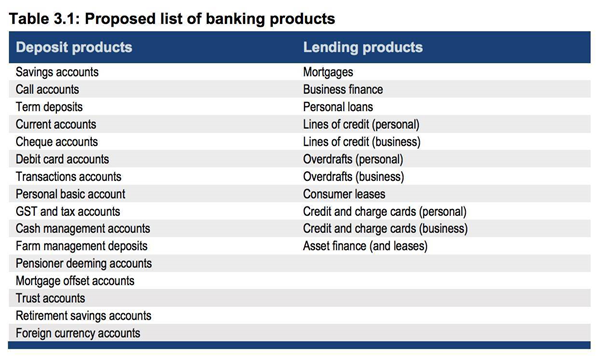

The review states that open banking rules will, however, be applied to 27 types of banking products.

Banks would have to provide data to customers about these products under an open banking scheme.

Some parties had wanted data subject to open banking to be limited to set “use cases”; however, the review found this unduly limited the scope of the project, and put too much power in the hands of institutions, rather than customers.

If the review’s plans are adopted, the open banking regime would be jointly overseen by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) and the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC).

The ‘big four’ banks would be the first to be subject to the rules, and would have a year to comply from a date yet to be set by the government.

Based on current timing, open banking would not be in place before mid-2019.

Scoping infosec

Any party wanting access to the data would need some form of accreditation, and there’s still debate on who would oversee that, how much it would cost, and how high to set the bar.

“Submissions have almost universally advocated some form of assessment and accreditation before non-banks should be allowed to participate in open banking,” the review found.

“The challenging question is: how stringent do the security and governance standards need to be?”

There also remain open questions about data security in an open banking arrangement.

The review was concerned that placing “too great an emphasis on privacy and security could delay or even undermine the effective introduction of open banking".

“It is therefore important that the nature and character of the potential risks be examined objectively and that the risks and opportunities are adequately balanced in designing the system,” it said.

Some of the risks include having customer data stored in many places, increasing “the number of potential stages at which data can be compromised — by being hacked or subject to unauthorised access or disclosure".

“Similarly, transferring data more often increases the possibility of that data being intercepted or inadvertently sent to an unauthorised party, or the wrong data being sent to an authorised party,” the review noted.

It remains an open debate topic on how secure non-banks would need to be in order to gain accreditation to handle data under an open banking regime.

Banks have high levels of security because they handle both money and information, the review noted. Handling only information may mean it is “not ... necessary for smaller open banking data recipients to match the standards set by banks precisely".

It is likely that security standards will be set later in the process. This would likely fall to a “data standards body”, whom the review suggests could be Data61, or failing that the ACCC.

The actual sharing of data would be done via APIs. The review recommends looking to UK rules on open banking as a technical starting point.

No charge would be levied on customers that sought data transfers between open banking participants.

Further, regulatory costs arising from the scheme should be “funded from general taxation revenue at the outset” rather than seeking to recoup them immediately from industry.

Where it falls over

The review also deals with the potential for banks or others holding customer data to refuse requested transfers, or for parties to deal with data above their accreditations.

In addition, it briefly examines which oversight organisation would field complaints.

One option it raises is for the creation of “a new Consumer Data Agency to hear individual and small business (up to a turnover of $3 million per annum) complaints".

“However, this option would involve significant, and costly, duplication of existing functions,” it noted.

“The OAIC currently handles complaints regarding private information, including the private information of small business owners in relation to their business activities. However, the OAIC does not handle complaints regarding the confidentiality of small business information, though this may exist within the same data set.

“Given that, from an individual trust perspective, the more serious of privacy, confidentiality, and competition issues, are likely to be privacy issues, the government may consider it appropriate for the OAIC to fill the role of this complaint handling body.”

_(20).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(33).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(23).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Benchmark Awards 2026

iTnews Benchmark Awards 2026

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

The 2026 iAwards

The 2026 iAwards

_(1).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)