4. Iridium

Shaun Nichols: Anyone who has ever had to deal with patchy mobile phone coverage and dropped calls can see the appeal of satellite phone networks that offer global coverage.

While the idea of Iridium was a dream for users, the reality was a nightmare for everyone involved, particularly the investors who pumped billions of dollars into the company.

Launched with great promise in 1998, Iridium was a mobile network that would cover the entire globe. Just nine months later it had to file for bankruptcy protection. The problem was in the 77 orbital satellites on which the Iridium network relied.

As you're probably aware (and Iridium seemingly wasn't) launching a satellite into space is very expensive. Launching 77 satellites into space is very expensive times 77. The company had nowhere near enough capital to deploy the satellites while still building a user base, and those debts soon became far too much for the company to handle.

The operation was eventually resurrected and carries on today as a specialist service for remote applications such as ocean vessels and rescue operations, but Iridium was never able to recover from its huge debts.

Iain Thomson: Ever since Arthur C Clarke proposed satellite communications, the promise of a united world has been marred by one fact: the cost of getting the damn things up there in the first place. Escaping the gravity well is an expensive business.

Iridium was a brilliant idea, spawned at the heart of dotcom optimism about how the internet and communications would change the entire structure of human society. Motorola, Al Gore and a host of big name backers got behind the scheme, and before long the rocket's red tails were burning.

However, like many brilliant ideas it glossed over the facts that such a system would be expensive and wealth is highly concentrated around the world, so what's the point of serving it all from a capitalist point of view?

Also the cost of maintaining a network that large in low Earth orbit, with a high risk of collision or malfunction, seems not to have been considered. Billions of dollars were spent before the company declared bankruptcy and the entire operation was bought by private investors for just US$25m.

Iridium is still running today, principally as a US military communications system, but I suspect we're 20 years and a hell of a lot of engineering away from an affordable satellite communications system.

3. Itanium

Iain Thomson: I can remember sitting in the keynote at the Intel Developer Forum when the company announced Itanium in 2001. It was big news - Intel's first 64-bit chip - and my fingers were furiously typing as Craig Barrett extolled the future of the chip, when it would power everything under the sun and the world would be a better, faster place.

But sitting at the back of my mind was a red flag. No-one was writing 64-bit code yet, and what IT manager in his right mind would want to do a complete hardware and software refresh just for a bit of extra speed? We were in the middle of the dotcom bust, and funds were so tight people were posting job ads reading 'Will code for food.'

At the end of the presentation I sat down with a good friend (who now runs a rival news site) and we rehashed the details before the conversation petered out. "It's never going to work," he said. "Not in the short or medium term."

"You're right," I replied, "But it's going to be fun trying to see them talk their way out of this one. Intel's put billions behind this. It's too big to fail."

Sure enough the market wasn't ready to make such a drastic change, and AMD's Opteron chip, which combined 32-bit and 64-bit operations, showed how it should be done. Opteron beat Itanium and Intel was forced to rush out the Xeon to make ground.

Shaun Nichols: Intel refuses to give up, but it is increasingly looking like the window for Itanium has closed. Developers still haven't really jumped onboard, and advances in x64 technologies have begun to bring the chips into the areas that Itanium was banking on for its success.

Much like IBM with the PS/2, Intel learned the hard way that you can't simply shift the entire industry onto a new platform by mandate alone. Intel tried to tell everyone that we're all going to move to 64-bit now, and developers ignored the call.

Without software support, Itanium had little appeal to the market. By the time the industry was ready to move to 64-bit, x86 processors had caught up.

One of the biggest problems the tech industry has is the ability to differentiate between 'Can we do this?' and 'Should we do this?' Itanium was a textbook case of engineering optimism outweighing business sense.

2. Sony battery recall

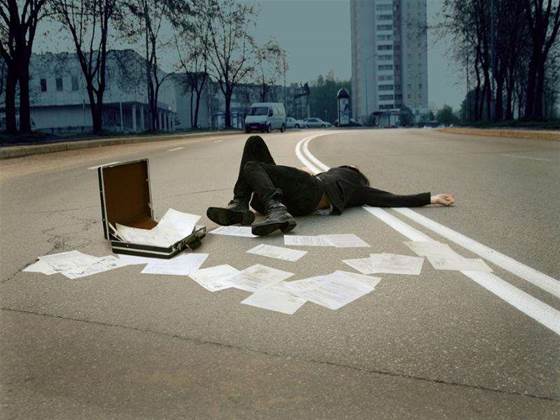

Shaun Nichols: Most of the cock-ups on our list led to user frustration and, in the worst case, losses of large amounts of money. But Sony's 2006 and 2007 battery fiasco was a mistake that put lives in danger.

The issue stemmed from manufacturing flaws in the lithium-ion battery packs Sony manufactured for companies such as Dell, Acer and Apple. If bumped or dropped hard enough, the packs were prone to damage which could cause battery cells to heat up to the point of violently combusting.

In other words, the battery packs had a nasty habit of exploding into flames. With the help of news reports and circulating internet videos, the otherwise rare condition became a major issue.

One by one, vendors began to demand recalls and Sony eventually ended up taking the hit for replacing 4.3 million battery packs. The recall dealt a major financial blow to Sony and was the second largest recall in the history of the computing industry.

Iain Thomson: The IT world had been talking about exploding batteries for years before anyone took it seriously. Anyone who's used laptops knows how hot they get and there's always something at the back of your mind that suggests you're one malfunction away from a skin graft. But then pictures and video surfaced online.

When you look at what's actually in a lithium-ion battery it can be rather a shock. Basically you've got a lot of fairly combustible fluid and some electrical igniters, and if a spark forms in there you'll have molten liquid poured over very sensitive parts of the human anatomy. It's no wonder there was such a panic.

That said, the scare also served a useful purpose in reminding people how much the industry is homogenising these days. The Sony battery recall didn't just cause Sony to pull back its batteries; a host of other companies Sony supplies had to do the same.

We forget that behind every 'individual' laptop are three or four companies, using multiple manufacturer's components, to build a computer that has a brand stamp on it. A flaw in one manufacturing process affects us all.

1. Intel Pentium floating point

Iain Thomson: The Intel floating point fiasco was a perfect storm of cock-ups. A technology flaw met an engineering and PR mindset that couldn't cope and turned the whole thing into a pointless mass panic. It is now a textbook case of how not to do things in the industry.

In 1994 things were looking good for Intel. Its Pentium processor was riding high, with the latest processors capable of an astonishing 66MHz clock speeds. Then in October a mathematics professor contacted Intel about some problems he was having. He'd installed a few Pentiums in a system being used to enumerate prime numbers, but had been getting very dodgy results back ever since. Was it possible that the chips were faulty?

It turns out Intel already knew the answer. There was an error in the chip's floating point unit and the engineers had already spotted it, but had decided that as the problem wasn't an issue unless you were performing really high-level mathematical functions they'd sort it out next time rather than doing a recall.

It's a classic example of the engineering mindset, focusing on the practical rather than seeing the whole picture. There was no real problem for real world use, was the thinking, and if this was explained then people would take a rational viewpoint on it. However this neglected one crucial point: people are emotional and that makes us less than rational sometimes.

CNN got hold of the story and the scoop went mainstream. These days Intel's PR operation is a well-oiled fighting machine (in both cases of the word at the end of good launch parties) but back then the engineers still called the shots and engineers make lousy PR people. Intel said that it would replace any Pentium if the owner could show that they needed to use floating point functions.

Mass panic ensued. People who wouldn't know a floating point if it bit them on the backside became convinced that their processor wasn't reliable and raised a ruckus. The stock market panicked too, and Intel suffered a massive share price rollback, and a whole new series of jokes.

Q: How many Pentium designers does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: 0.99904274017, but that's close enough for non-technical people.

Eventually Intel backed down, but the whole fiasco cost the company US$450m in direct costs, a battering on the world's stock exchanges and a huge black mark on its reputation.

Shaun Nichols: Every time the tech sector heats up and we get a new wave of hot start-ups, those involved in the company wonder why anyone would want a stuffed-shirt business type to run the show.

Inevitably you get a incident like Facebook Beacon or Intel's floating point crisis and everyone realises that tech smarts don't translate to business smarts.

I think it also shows why the tech sector will continue to experience these sort of cock-ups over and over again. Engineers and developers love rational solutions, but it's not always the rational solution that is best.

Intel was right in that very few systems would ever encounter any problems with the floating point issue, just like Sony was right in that very few systems would ever be at risk of a battery meltdown.

The problem is that the market does not appreciate statistical probability. If you were to tell people that there was a 1 in 10,000 chance of something happening to their computer, most all of them would worry about it even though they know the odds of a failure are extremely low.

Techies may not like to work with, and under, the career suit types but for a company to succeed in the long term, it's vital that true business men and women take the reins.

_(28).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

.png&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Benchmark Awards 2026

iTnews Benchmark Awards 2026

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

The 2026 iAwards

The 2026 iAwards

_(1).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)