Australia's police and public safety agencies risk falling five years behind their global peers on technology if the Federal Government fails to allocate sufficient wireless spectrum for their exclusive use.

Mobile equipment vendor Motorola Solutions and the West Australian Police set up a small Long Term Evolution (LTE) mobile network in suburban Perth this week to show government regulators, public safety agencies and the media a variety of applications that could save lives and money if deployed on a wider basis.

Public safety agencies have lobbied in recent years for a dedicated chunk of the 'digital dividend' radio spectrum — particularly in the 700 MHz band — to be made available when analog TV services switch off by 2014.

But their calls have fallen on deaf ears in Canberra, where the Australian Government has indicated it will sell the spectrum in lots to the highest bidders — likely all or some of the three major mobile carriers — in order to gain a $4 billion dollar windfall.

The Government has argued that telcos can provide sufficient bandwidth to public safety agencies using commercial LTE services, and has opened up the possibility of using some of the 800 MHz band for exclusive emergency use instead.

Motorola Solutions managing director, Gary Starr, claimed that any useable chunk of the 800 MHz band was at least three to five years away, preventing Australia's emergency services forces from upgrading or converging their networks.

The 800 MHz band was also less favoured due to potential interference with consumer devices such as cordless phones and garage door openers, not to mention use of the 850 MHz band by Telstra and Vodafone Hutchison Australia for their 3G services.

Disadvantages

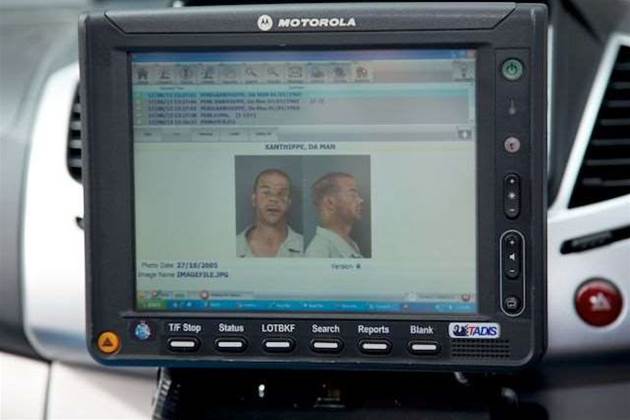

Starr told the press at the Perth demonstration that today's public safety applications tended to run on narrowband, pushing out text-based jobs into the field, with field officers making database inquiries stored centrally at command. These largely operated on 400 MHz spectrum, which is also under review by spectrum regulator, the ACMA.

WA Police, for example, makes use of a private radio network in metro areas, but roams onto public 3G networks in more remote areas.

Starr argued that a more advanced police force could consider data services as mission-critical, as public safety applications now rely on the use of digital mapping, video surveillance and higher definition images in the field, and other automated systems that consume large amounts of data.

The United States Government allocated $US7 billion to the construction of a dedicated public safety LTE network, built by Motorola, to ensure these applications could improve police efficiency.

But Australian politicians have instead argued that public service agencies might simply be given the power to kick consumers off public LTE networks during emergencies or to build temporary networks.

Starr acknowledged that Australia was unlikely to be able to afford the $7 billion capital cost the US has put forward to roll out its dedicated LTE network.

But he said that for a few hundred million dollars, Australia could build and maintain a network in large metro areas for 10-15 years.

"Usually when we look at public safety outcomes, it is hard to measure an economic return," Starr argued.

"But studies reveal that for one dollar spent on public safety agencies, there can be a four-to-five dollar return."

That return might be measured in paper processes or litigation avoided, reduced healthcare costs and the "force multiplier effect" that allows an agency to make decisions in the field quickly, rather than having to go back to central position to obtain information.

Applications

Starr argued that day-to-day scenarios warranted a dedicated network.

It could be used, for example, to enable police, fire and ambulance agencies to collaborate over live footage along a bushfire front, a flood-affected area or road accident. It could enable police cars in the field to scan upwards of 8000 license plates every shift in the search for stolen, unlicensed or other vehicles of interest, alarming officers only when exceptions are found.

It could be used similarly to commandeer privately-owned security cameras to monitor the scene of a siege.

Demonstrations highlighted the difference between a narrowband network today — which limits Police in the field access to databases of thumbnail-sized images of suspects over a 128 Kbps connection — and a 1290 x 960 pixel resolution live feed over 3.5 Mbps.

Similarly, demonstrations revealed a noticeable jump in quality when public safety agencies were allocated a 10 MHz x 10 MHz chunk of bandwidth, as opposed to the 5 MHz x 5 MHz assumed by Australian politicians to date.

"A purpose-built broadband network gives the coverage and capacity required, but also the ability to control and prioritise traffic," he argued.

"Now that 700 MHz is off the table, the spectrum will take three to five years to free up. But by then we expect the business case to be even stronger."

A representative from the WA Police Union was on hand to assure the press that public service agencies were desperate to access these new technologies.

The ACMA allocated a temporary license to build the one-kilometre-wide demonstration network between WA Police's Centre and the test site. Its staff have already toured the demonstration facility.

_(23).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

_(20).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

.png&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Executive Retreat - Security Leaders Edition

iTnews Benchmark Awards 2026

iTnews Benchmark Awards 2026

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

iTnews Cloud Covered Breakfast Summit

The 2026 iAwards

The 2026 iAwards

_(1).jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)